You aren’t just imagining the longer walk to Economy Class.

On a typical British Airways flight from Heathrow to New York JFK, both airports’ busiest route, you now pass through half the plane to get to the cheap seats[i]. In a Boeing 777 aircraft designed for up to 392 passengers, BA only fills it with 256 – 65% of the capacity[ii]. “Improving airline seating efficiency” may not be a rousing economic growth or emissions reduction initiative, but has more potential for new term impact than building new runways or using sustainable aviation fuels.

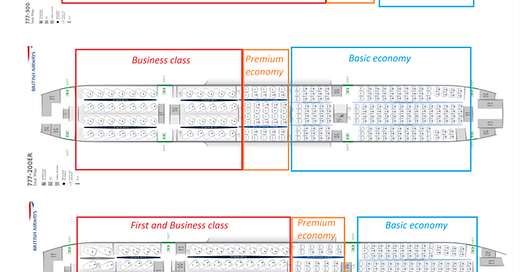

Seat Maps for British Airways 777 fleet (300, 200ER and 200)

Last week, the UK government backed the expansion of Heathrow airport via building an additional runway, as part of its agenda for economic growth. Calls for a Heathrow airport expansion have sounded for decades, initially approved in 2009 under Gordon Brown. The new iteration of the plan is controversial because of its impact on surrounding communities, some of which will be “partially demolished”, and its potential to increase carbon emissions at a time when the UK has made significant commitments to reducing them.

Heathrow is admittedly a very busy airport. It is the fourth most trafficked airport in the world according to OAG, attracting over 80 million passengers per year. A flight lands or takes off every ~90 seconds per runway on average. Compared to other mega-airports like Dubai and Atlanta, Heathrow has less breathing space in its schedule because of fewer runways or shorter operating hours, sparing nearby residents from round-the-clock noise.

Despite doubts raised over the economic benefits of a new runway, Heathrow Airport management certainly thinks it makes sense. While light on the details, their analysis shows Heathrow capping out at 90 million passengers per year with no changes, or 110 million if they upgrade the terminals but do not add extra flights. With a new runway, they claim they could accommodate almost 170 million travellers per year.

Building more infrastructure is in Heathrow’s interest as they can charge customers to earn a commensurate return on their investment. However, detractors like the New Economics Foundation say the runway may not be good for the UK. It could send more domestic tourism spending overseas, without necessarily attracting more business travel, and may not actually deliver much of the jobs growth that is promised.

If flight growth does materialise, the decision to expand Heathrow’s capacity is at odds with the government’s ambitious climate goals. The new runway could add 4 million tonnes of emissions per year. This is more than 1% of the UK’s total carbon emissions in 2023, or around 10% of the UK’s electricity emissions. This would partially negate the climate benefit of the government’s 100% clean energy target by 2030.

The government thinks it can tackle climate issues with initiatives like sustainable aviation fuels, the emissions trading scheme (ETS), and carbon removals, but none of these will be sufficient in the near term.

Sustainable aviation fuels are in short supply. Bloomberg analysis suggests that sustainable fuels will be able to supply just 5% of global fuel demand by 2030. They are also twice as expensive than conventional fuels and still emit carbon during production.

The UK emissions trading scheme, too, is not yet adequate. It covers emissions for flights leaving the UK to British and most European destinations, excluding more carbon-intensive long-haul flights like our New York journey. This means just 8.8 million tonnes of recorded emissions in 2023[iii] are covered by the trading scheme, out of an estimated 32 million tonnes for all destinations. For BA, 2.4 million tonnes, or just one sixth of BA’s 15 million tonnes of emissions, were covered under UK and EU ETS schemes[iv].

Airlines also still receive some free emissions to prevent “carbon leakage”, a euphemism for allowing companies to emit carbon to remain competitive. This means that although the headline figure for traded carbon emissions in 2023 was £53 per tonne on average, airlines paid this fee on 51% of the emissions in scope[v]. Across all UK emissions, Transport and Environment estimates that airlines were charged just £8 per tonne emitted, and that the government could have earned £1.4 billion in extra revenue if all emissions were included in the scheme.

While it is early days for carbon removal technologies, they are far more expensive than even the ETS and therefore likely to be used even less in the near term. In 2024, BA negotiated a landmark £9 million deal for 33,000 tonnes of carbon removals over six years, implicitly pricing emissions at £273 per tonne. The annualised amount purchased would have covered just 0.04%, or 3 hours’ worth, of the company’s emissions in 2023.

Which brings us to plane utilisation. Civil Aviation Authority statistics report seat loading on Easyjet and British Airways at 88% and 84% respectively[vi], which seems relatively high. Yet this is based on the available seats that the airline has offered, not on the total capacity that a given plane can accommodate.

Seat utilisation on largest British carriers (30% passengers, 18% flights)

Using manufacturer specifications for seating capacity, BA is only operating at a utilisation of around 70%, compared to Easyjet at 84%[vii]. The seating plans for Qatar Airways, Emirates, and American Airlines (top airlines on the UK’s most popular routes) show a similar pattern of large floorspace allocations to business class seating.

If BA and other airlines marketed a seating plan with more economy and fewer business seats, they could reduce the number of required flights by as much as 30%. This would free up capacity for other aircraft or increase traffic on existing routes. It would also reduce the carbon emissions per passenger.

Here lies the rub. “Planes are designed by accountants, not engineers,” as my father, a pilot, always said. This used to describe cramming as many passengers into a space as possible. Instead, it seems premium airlines like BA are expanding their business class because it optimises revenue.

Companies can potentially earn more per flight by increasing the floor space for business class tickets, which can sell for up to twenty times as much as an economy fare. Even offering these seats at a “bargain” (e.g., only three times more expensive, like current LHR-JFK tickets) might induce some customers to upgrade and fill up the cabin, earning the airline more than their equivalent in economy seats. Airlines are not charged for most of their emissions, meaning under-loaded flights are not significantly penalised. The government may want more passengers to stimulate growth, but airlines just want more profit per flight.

Perhaps the new government is not too bothered by this. Airlines may argue that more space for expensive seats is what the business travellers want, and subsidises low-cost travel for everyone else. And anyone who has waited for baggage at Heathrow can imagine the benefits from the terminal upgrades that would come with an extra runway. Meanwhile, getting new airport infrastructure built is a visible win for the government’s growth agenda. The investment will create jobs, at least during construction. Even though this impact won’t materialise for a decade at least, when it finally does they may be able to say that more flights and passengers landed in the UK as a result of their efforts.

Yet if we don’t interrogate our air travel habits, like the ever-expanding business classes or the inadequacy of existing decarbonisation approaches, airport expansions may increase aviation pollution without much uplift in passenger numbers. If what the government cares about is the economic spillovers from getting more passengers travelling to and from the UK, and doing so without a severe environmental impact, we don’t necessarily need more runways. We could do with more of the cheap seats.

[i] First, business and premium economy take up half the plane on 777-200ER flights and more than half on a 777-300.

[ii] Boeing’s 2-class seating plan. Total flight capacity is higher if single class (i.e. all economy seats). BA typically operates 3-4 classes on their flights.

[iii] A similar scheme is in place for flights originating in Europe.

[iv] 1.3 million tonnes under the UK ETS and 1.1 million by the EU ETS + Switzerland, including BA Cityflyer and BA Euroflyer.

[v] Calculated by dividing allocated emissions by total surrendered emissions.

[vi] Calculated using number of seat kilometres used divided by number of seat kilometres available. Table 1.11.2 of airline data, 2023.

[vii] Author’s calculations using seats filled per flight (CAA) divided by aircraft capacity (1 or 2 class seating arrangements for Boeing and Airbus models).

Really interesting read Lucy!